Pan African flags used at the Million Man March 20th Anniversary. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Black World/Negro Digest May 1975. Vol. XXIV No. 7. The Johnson Publishing Company.

The Pan-African Voice journal, volume 2, August 1968. Pan African Students Organization in the Americas, American, 1960 - 1977

The pan-African movement ; a history of pan-Africanism in America, Europe, and Africa by Imanuel Geiss, 1974

Flyer announcing a protest against apartheid in South Africa. 1977. Pan African Students Organization in the Americas.

Flyer announcing a demonstration on African Liberation Day. April 1972. Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

B.L.A.C. (Black Liberators for Action on Campus), University of Nebraska at Omaha, https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.36610140

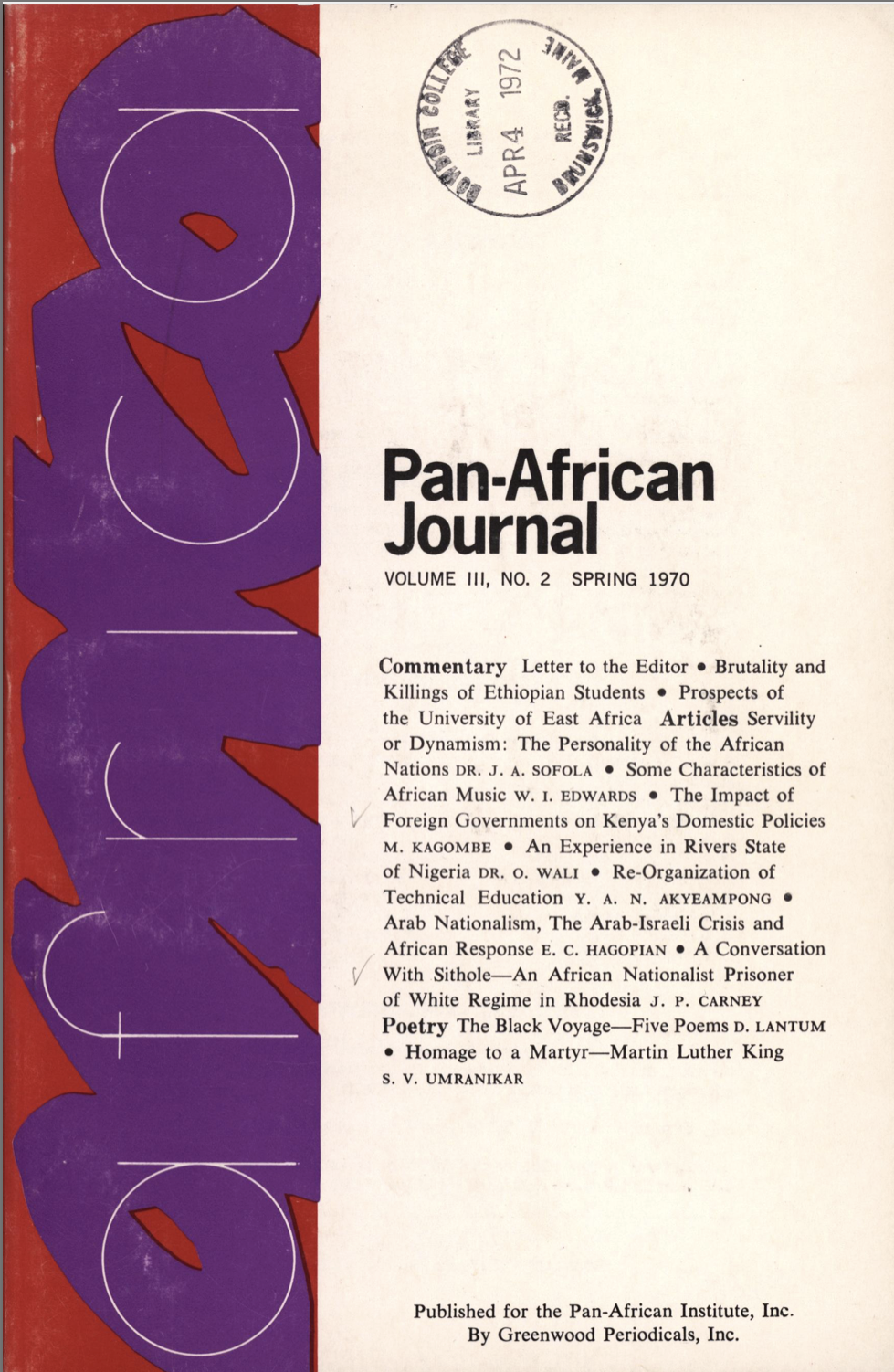

Pan-African Journal, Reveal Digital, 04-01-1970 https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.39990662

Stokely Carmichael, Kwame Nkrumah, and Shirley Graham DuBois 1967. Image courtesy of the Thabo Mbeki Foundation.

Manufactured by AFL-CIO, American, founded 1955, and Owned by Jan Bailey, American, 1942 - 2010. Pinback Button of the Pan-African Flag. after 1955. Metal, Diameter: 1 × 1/4 in. (2.5 × 0.6 cm). National Museum of African American History and Culture; Collection of the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture. https://jstor.org/stable/community.31886907.

University of Salford Students Union. Pan African Society General Meeting. 1988. https://jstor.org/stable/community.34588156.

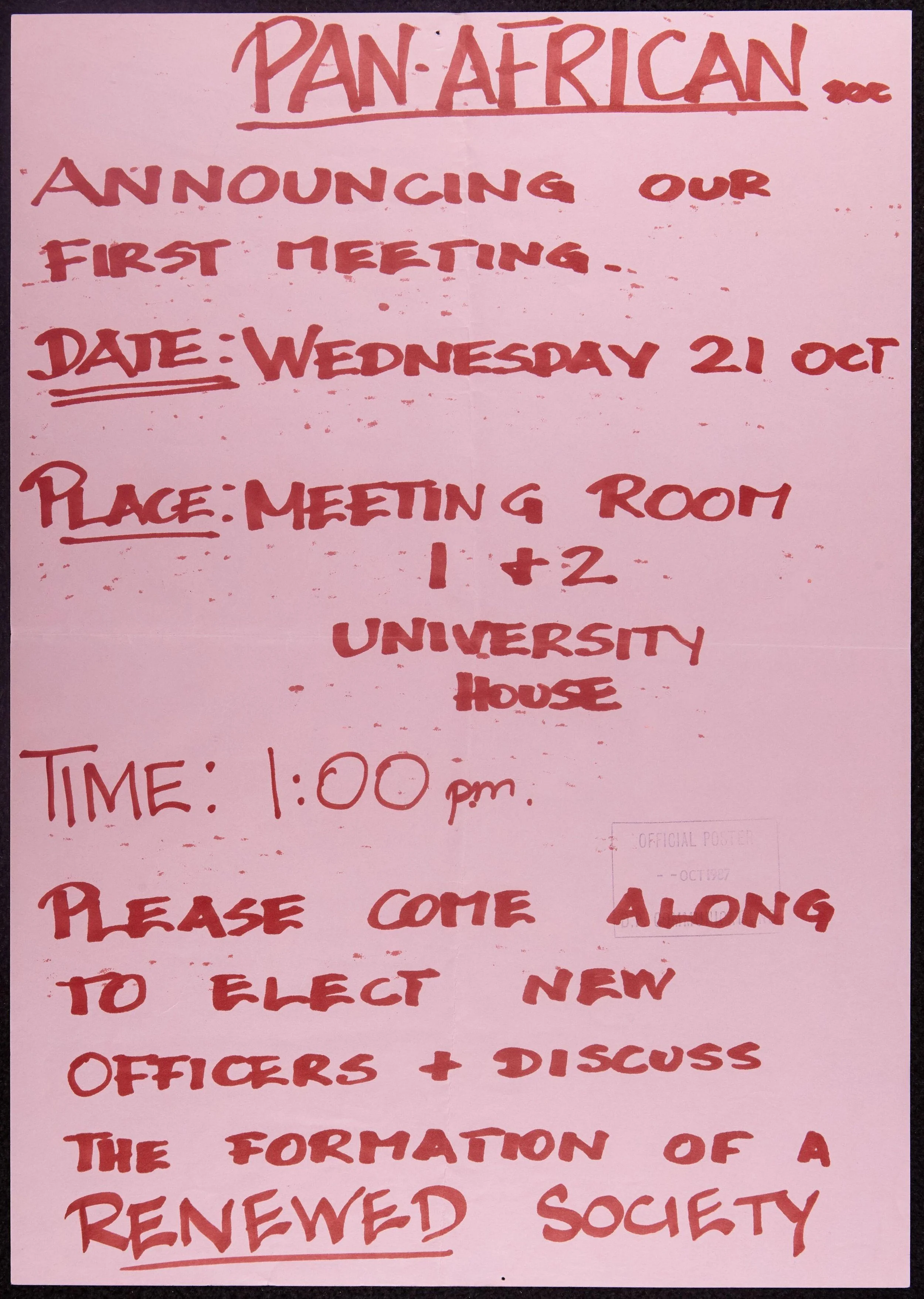

University of Salford Students Union. Pan African Society First Meeting. nd. https://jstor.org/stable/community.34588064.

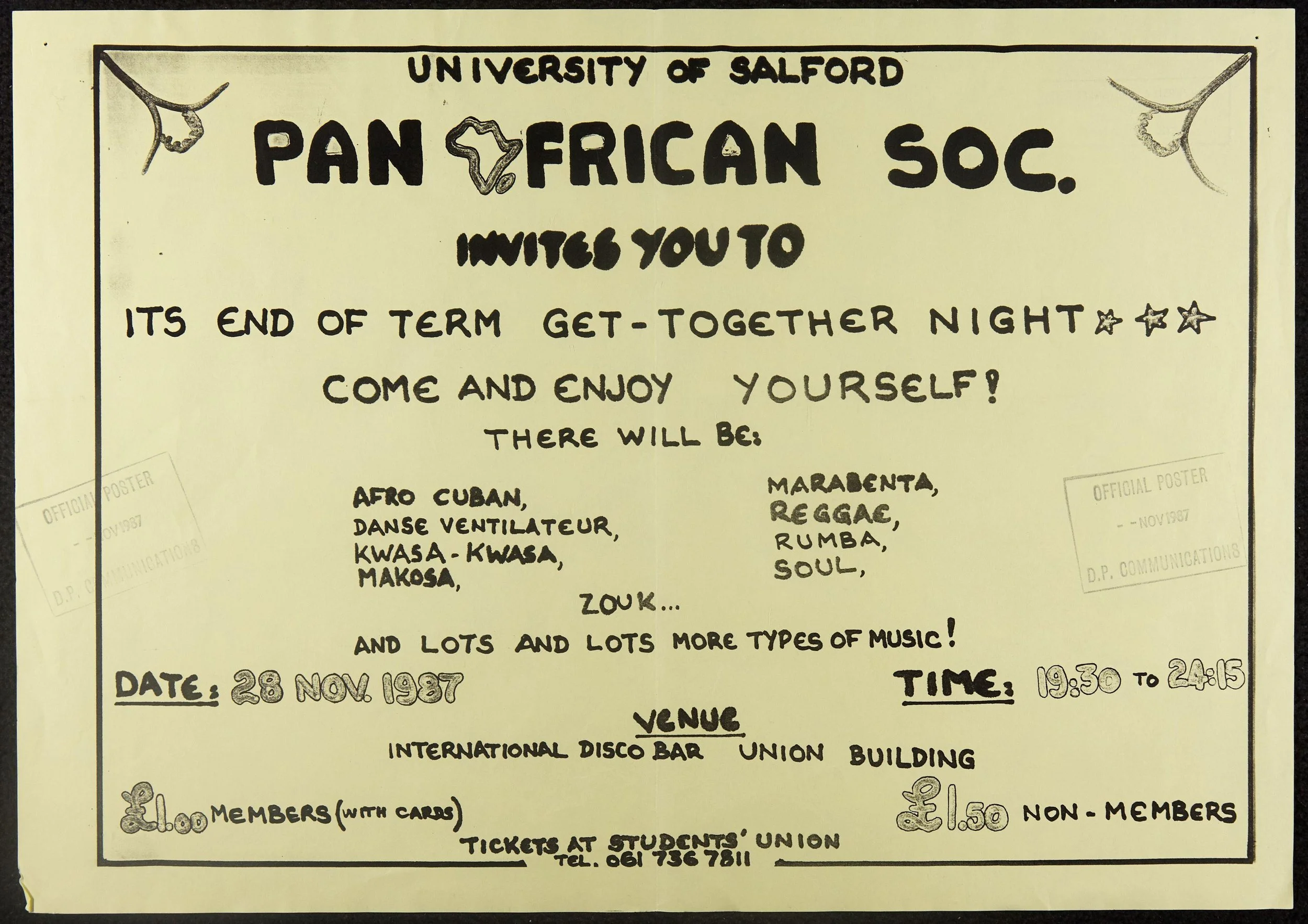

University of Salford Students Union. University of Salford Pan African Society. 1987. https://jstor.org/stable/community.34588082.

1. Official poster of the First World Festival of Negro Arts (Dakar, 1966). PANAFEST Archive. 2. Official brochure for the First Pan-African Cultural Festival (Algiers, 1969). PANAFEST Archive

FRELIMO delegation in attendance at the First Pan-African Cultural Festival (Algiers, 1969). Photo Luc-Daniel Dupire / PANAFEST Archive.

Free Jazz pioneer Archie Shepp on stage at the First Pan-African Cultural Festival (Algiers, 1969). Photo Luc-Daniel Dupire / PANAFEST Archive.

Brochure cover announcing FESTAC (Lagos, 1977). PANAFEST Archive

Congress: Manchester and the Fight for Equality, Black History Month, Collections, Current Activities. Copyright © 2019. Ahmed Iqbal Ullah Education Trust. All Rights Reserved. Registered Charity.

The 1st Pan-African Congress, Paris, France, February 19–22, 1919. Copyright © 2019. Ahmed Iqbal Ullah Education Trust.

GB3228.34/1/2, Pan-African Congress 1945 and related celebratory events 1982-1995, Press photograph of the 1945 Pan-African Congress delegates and [Manchester City Mayor?] (1945).

Julius Nyerere and Dr Hastings K. Banda Prime Minister then president of Malawi, visiting Tanganyika in the early 1960s. (Credit: The National Archives -United Kingdom)

Looking back to move forward: The first Pan-African Cultural Festival in Algeria, 1969.

Black Transnational Movement for Representation and Land Ramla Bandele, Article Author, The 1919 Pan-African Congress. Via wwiafrica (Tumblr).

Black Transnational Movement for Representation and Land Ramla Bandele, Article Author, The 1919 Pan-African Congress. Via wwiafrica (Tumblr).

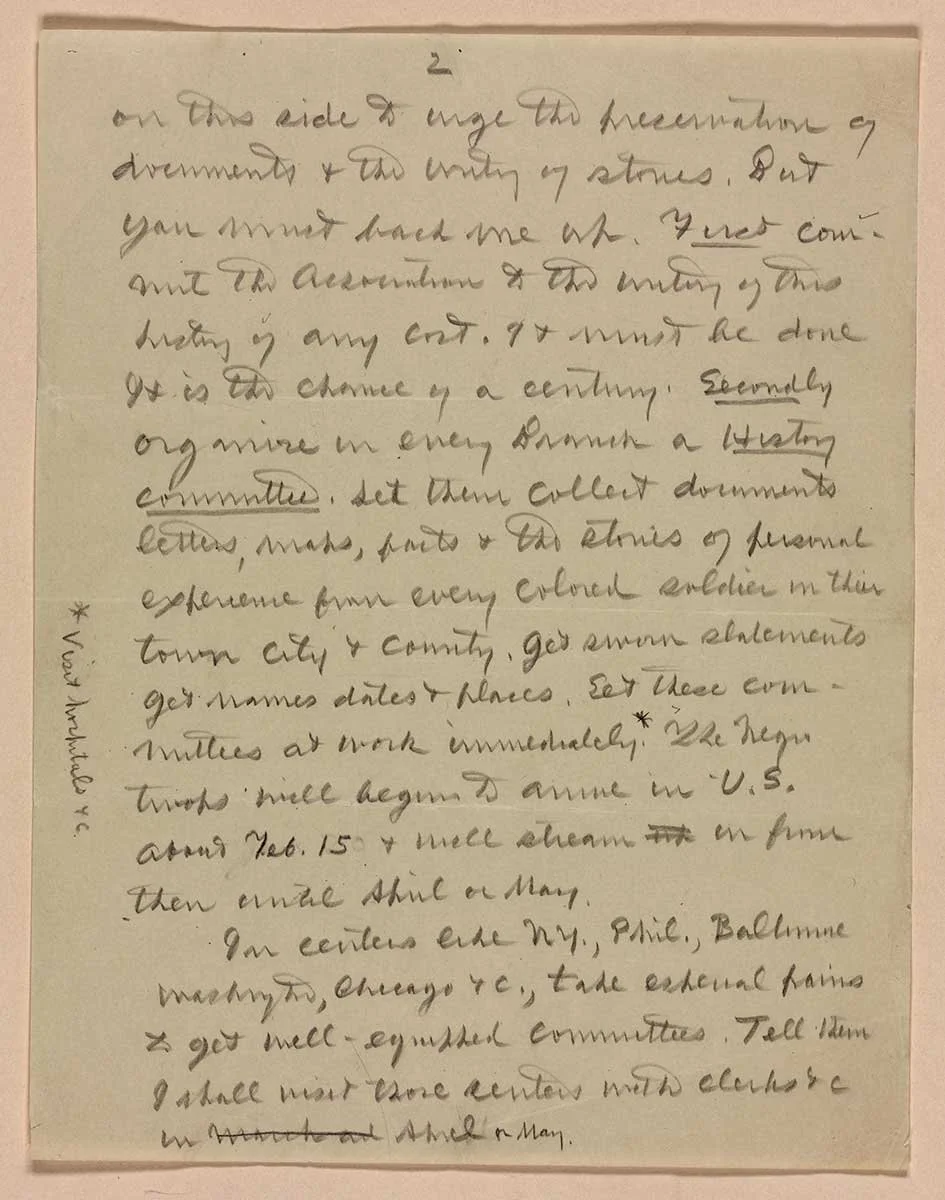

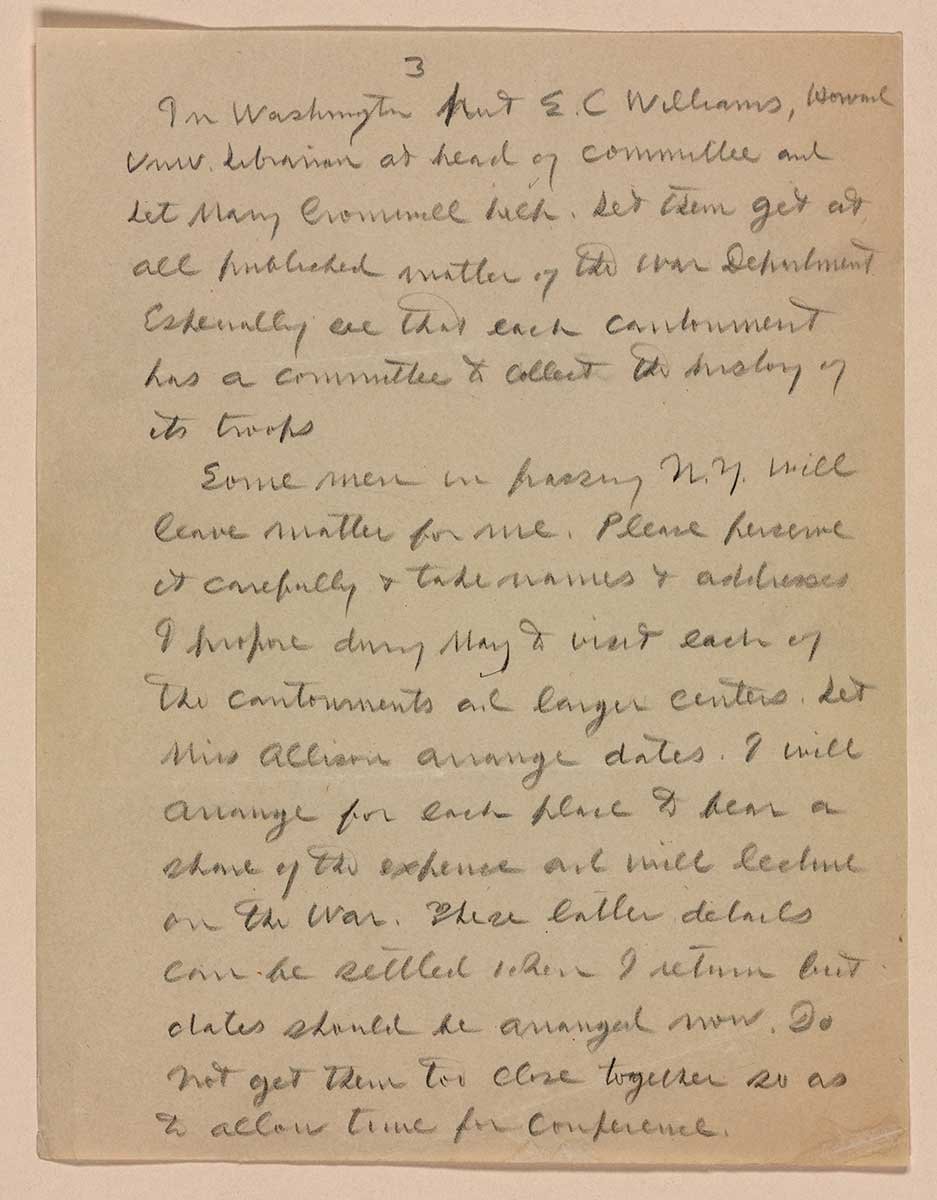

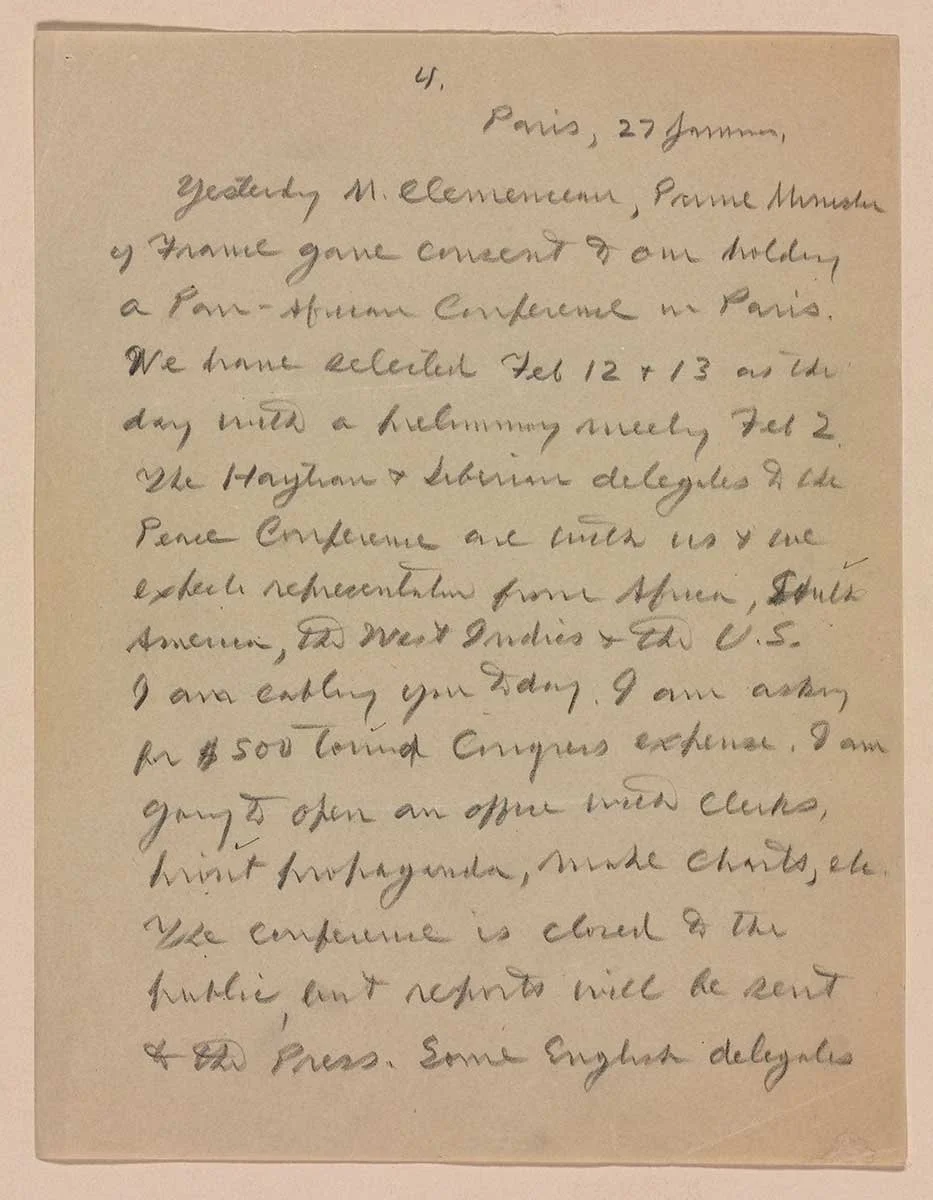

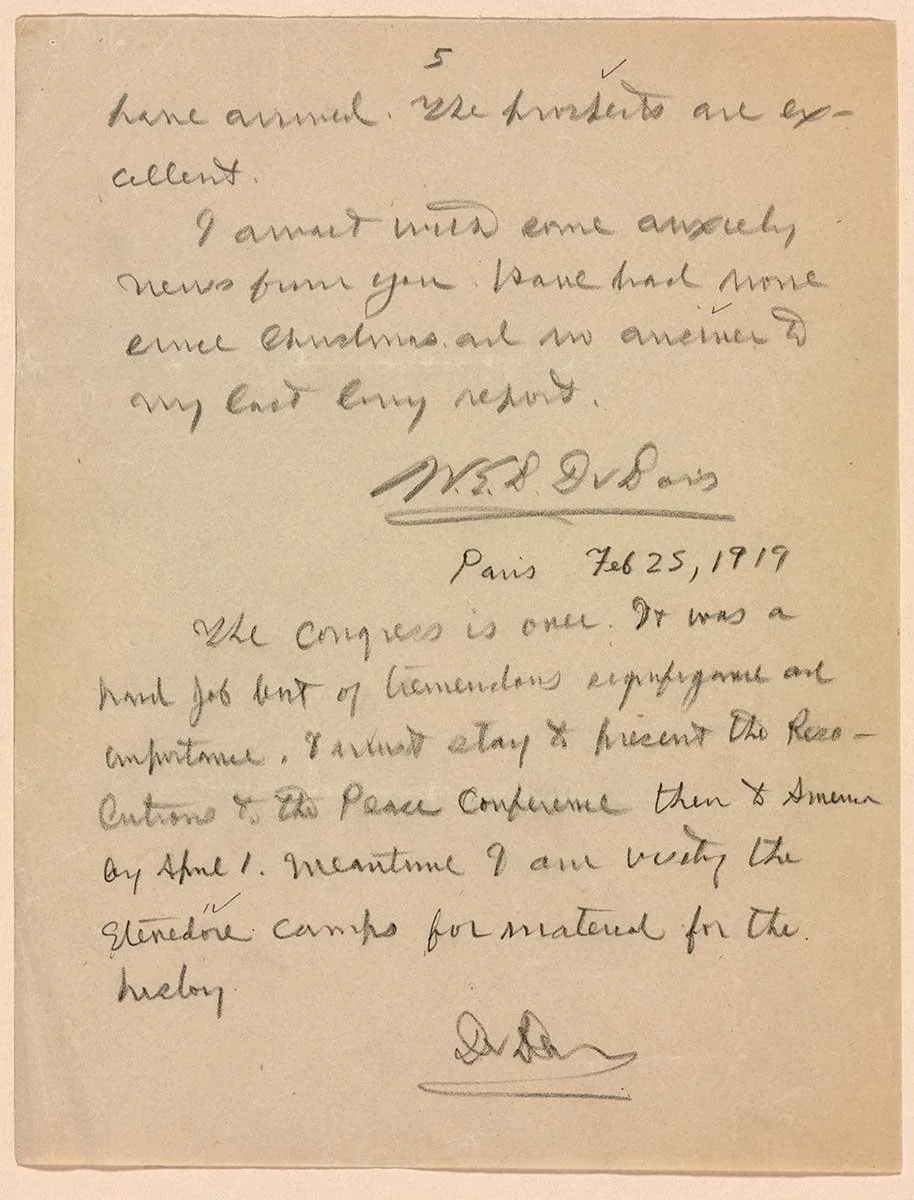

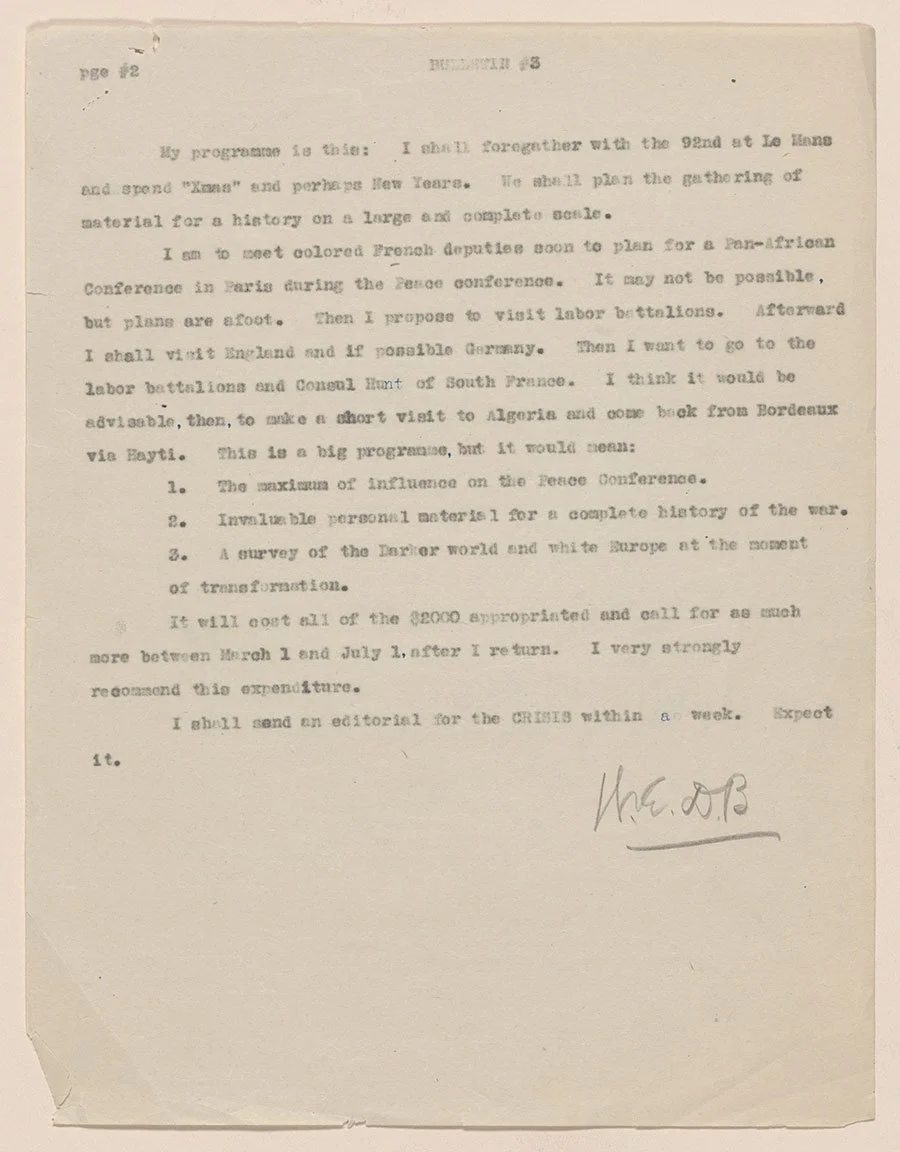

W. E. B. Du Bois to the NAACP, January 12, 1919. NAACP Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (175.00.00, 175.00.01)

W. E. B. Du Bois to the NAACP, January 12, 1919. NAACP Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (175.00.00, 175.00.01)

W. E. B. Du Bois to the NAACP, January 12, 1919. NAACP Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (175.00.00, 175.00.01)

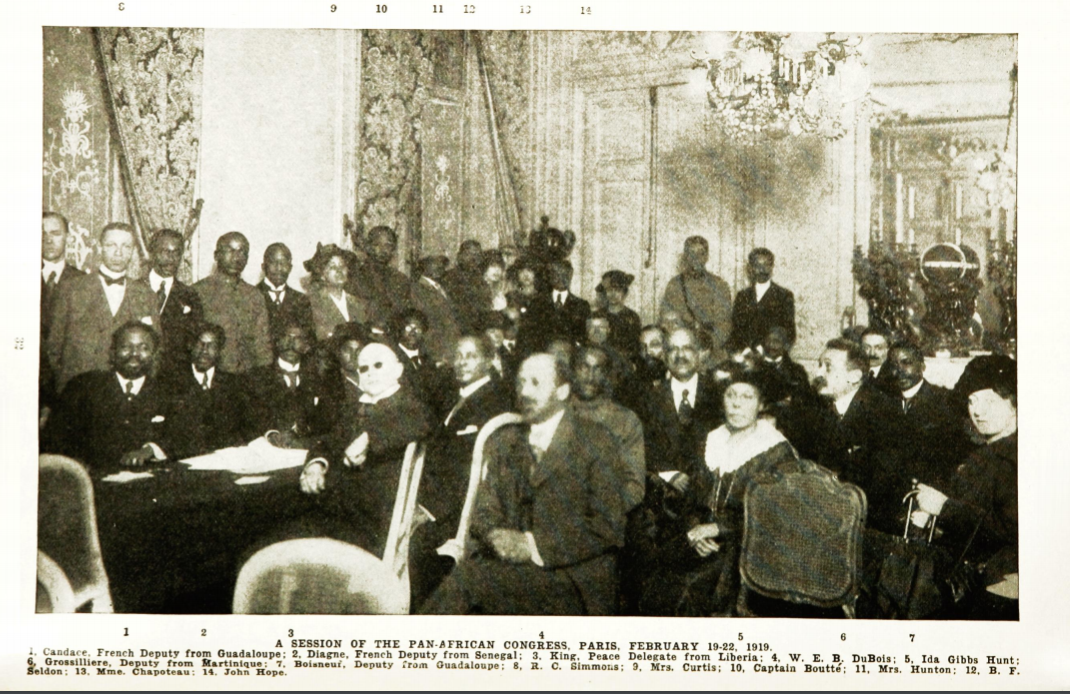

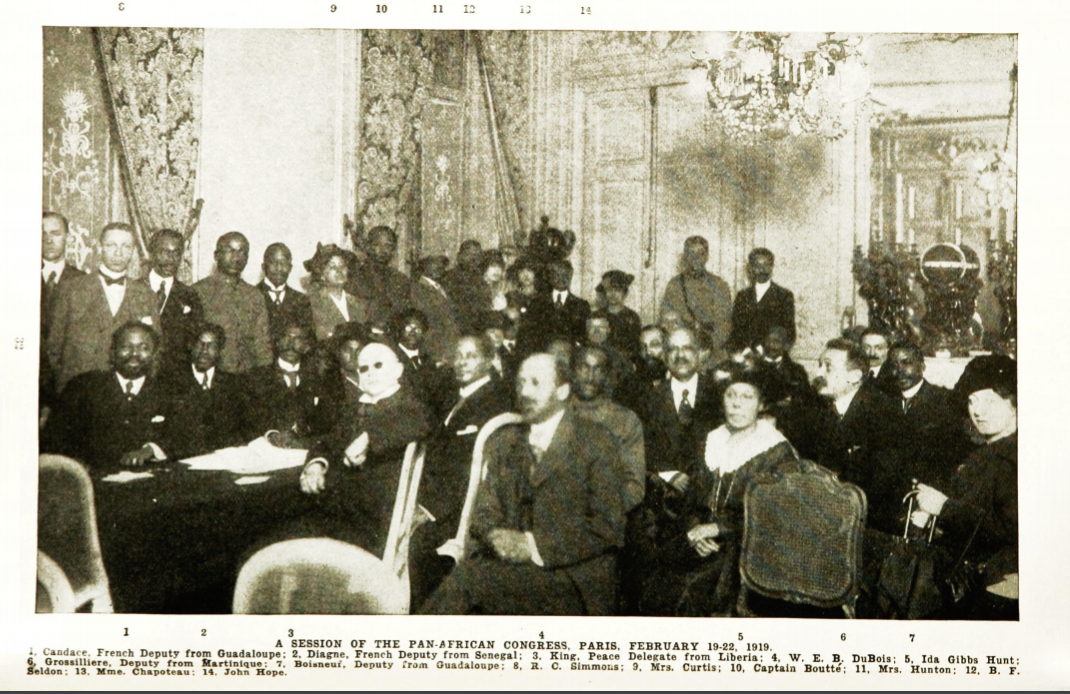

!["A Session of the Pan-African Congress, Paris, February 19–22, 1919" in The Crisis, A Record of the Darker Races. [Reprint] NY: Arno Press, 1969. General Collections, Library of Congress (174.01.00)](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/65b41067c4042363cf11625f/f960ed08-cf6b-42a1-b18e-13e99a1bb2f2/paper6.jpeg)

"A Session of the Pan-African Congress, Paris, February 19–22, 1919" in The Crisis, A Record of the Darker Races. [Reprint] NY: Arno Press, 1969. General Collections, Library of Congress (174.01.00)

W. E. B. Du Bois to the NAACP, Bulletin #3, January 1919. “My programme is this. . . . I am to meet colored French deputies soon to plan for a Pan-African Conference in Paris during the Peace Conference.” NAACP Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (175.01.00)

Delegates from Oregon for the Fourth Pan African Congress in New York, 1927.

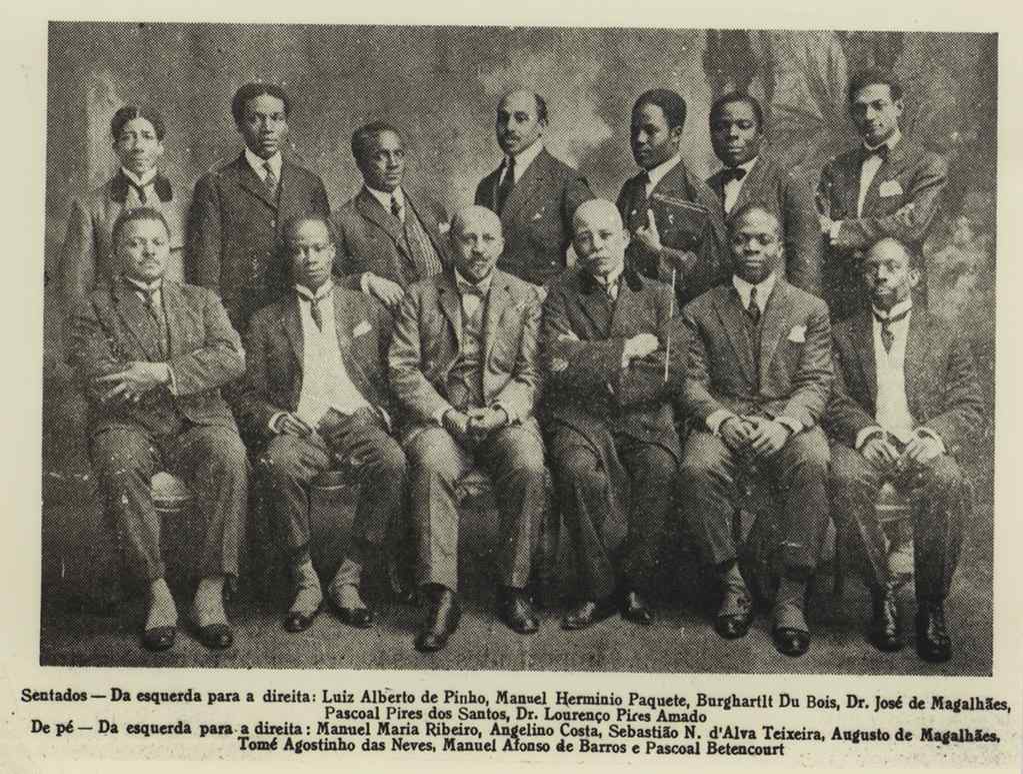

Delegates of the 1923 Pan-African Congress, Lisbon.

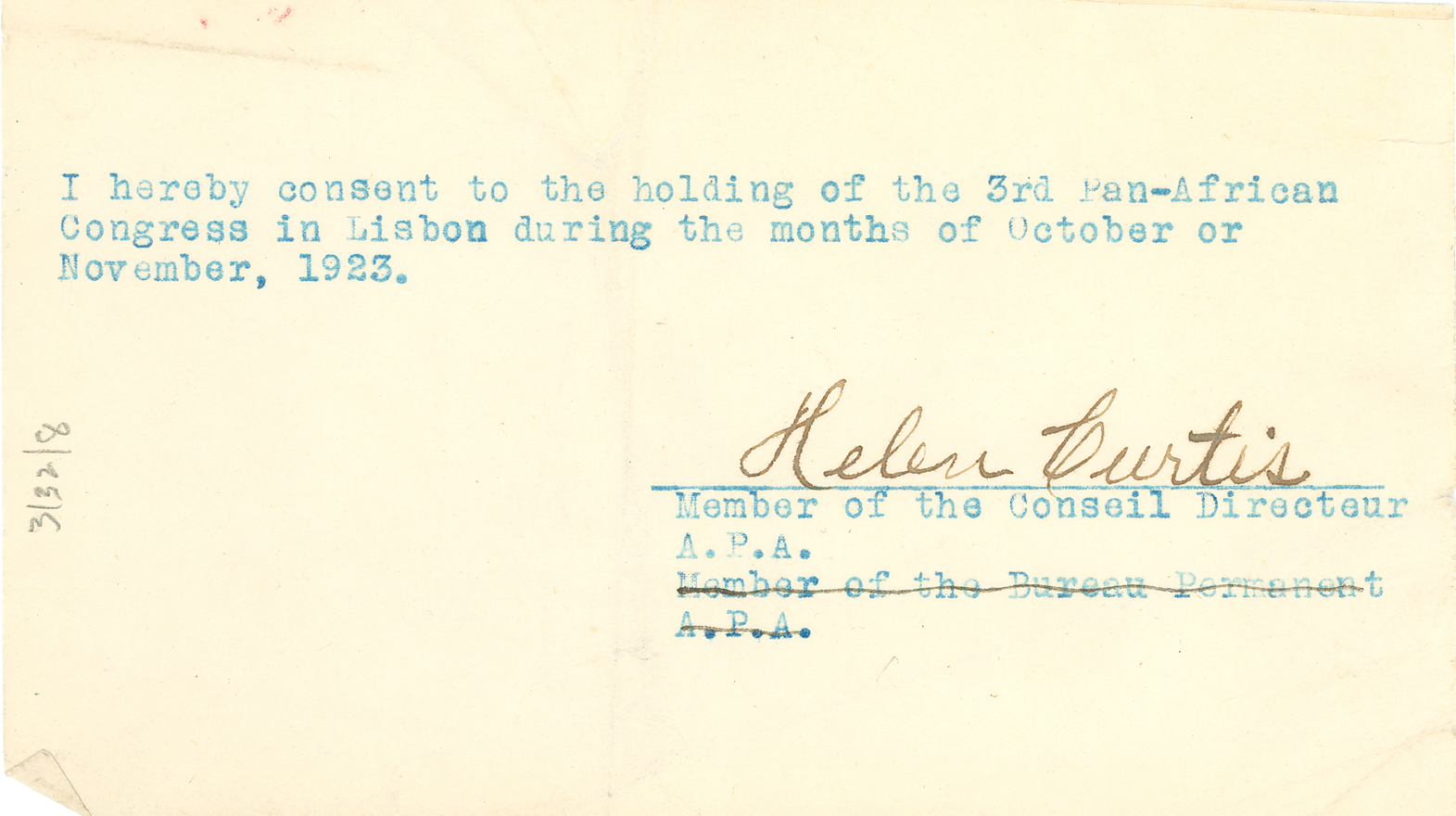

Helen Noble Curtis – Agreement to hold the third Pan-African Congress in Lisbon, 1921

Pan-African Congress in Paris, February 19–22, 1919.

Members of the Second Pan African Conference, Brussels, 1921.

Session in the Palais Mondial, Brussels, 1921

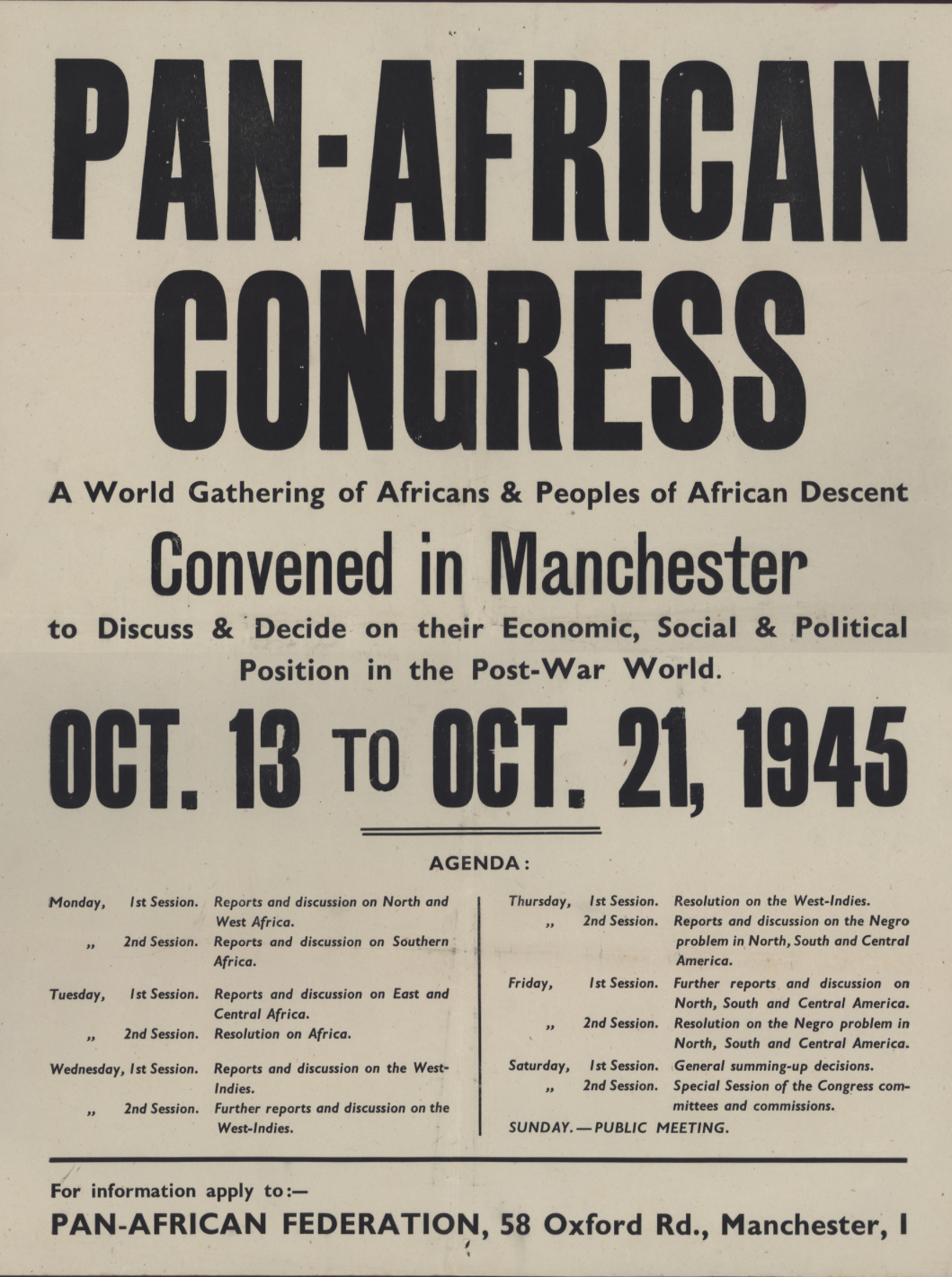

Pan-African Federation, Pan-African Congress poster, ca. October 1945. All rights for this document are held by the David Graham Du Bois Trust. https://credo.library.umass.edu/view/full/mums312-x01-i075

The Pan-Africanist Movement and the road to liberation, African Union. https://oau60.au.int/en/pan-africanist-movement-and-road-liberation

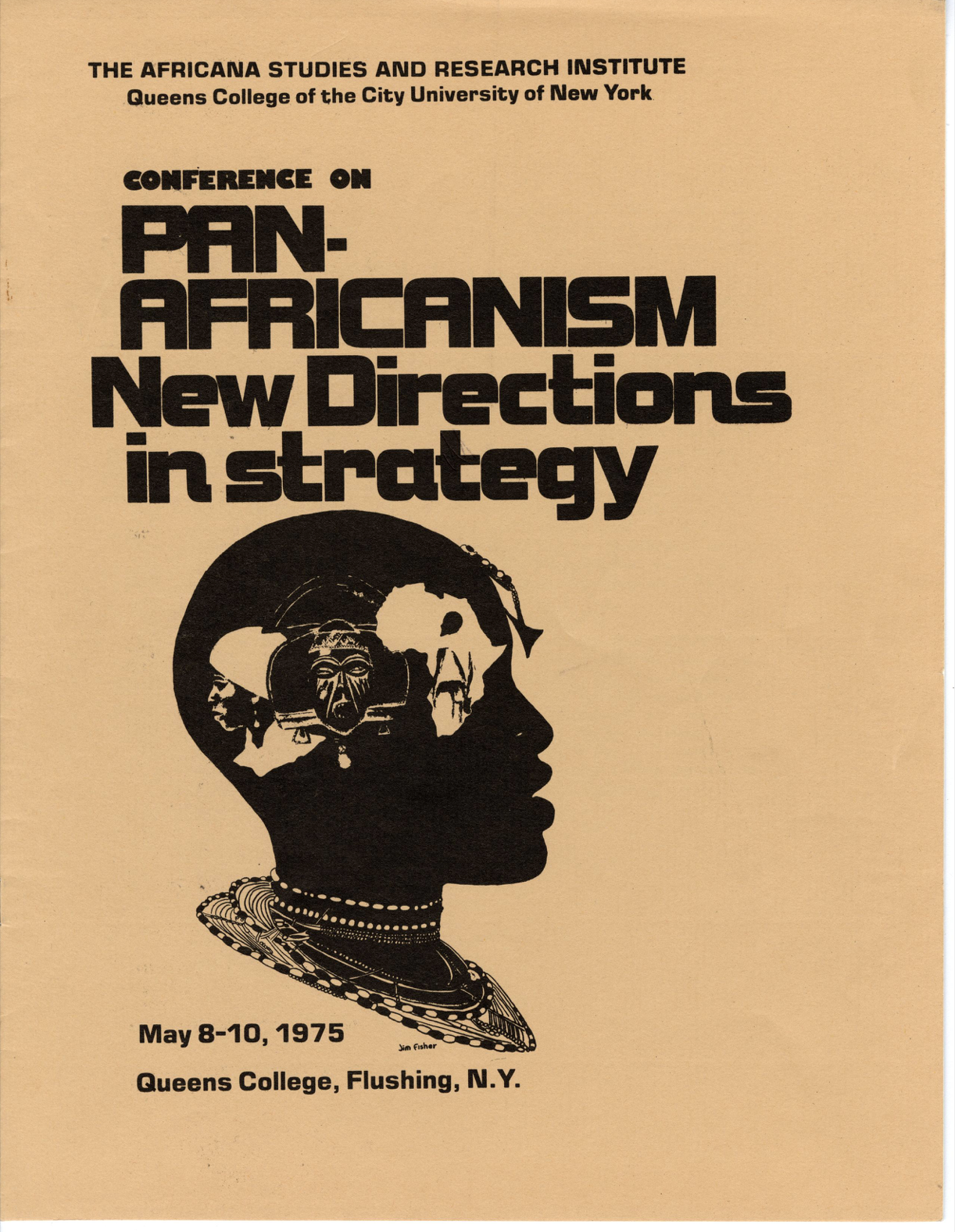

Conference on Pan‑Africanism: New Directions in Strategy. Queens College. JSTOR, stable URL https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.37765569. (Cover)

Conference on Pan‑Africanism: New Directions in Strategy. Queens College. JSTOR, stable URL https://www.jstor.org/stable/community.37765569. (Page 1)

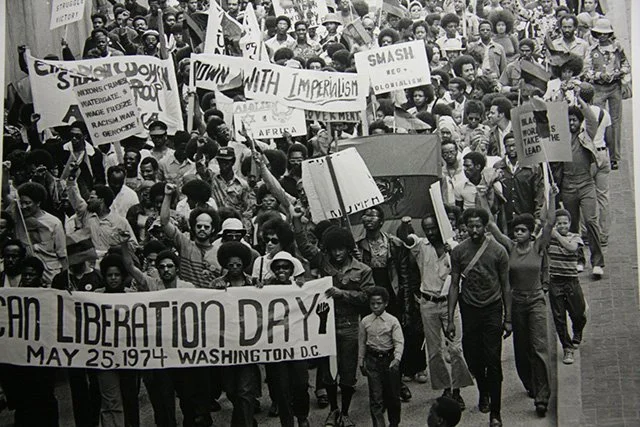

Anti-imperialism march on African Liberation Day, in Washington, DC, in a photo taken in May of 1974. (Photo: Risasi Zachariah Dais). Pan-Africanism: The Silver Bullet in the Heart of Empire by Ian Scott (Hood communist)

Spearhead cover, Nov 1961. Presented by Katharina Föger Eric Burton. "Spearhead. The Pan-African Review was established by the South African lawyer and journalist Frene Ginwala in Dar es Salaam, the capital of Tanganyika (later Tanzania), just one month ahead of the country’s full independence in December of 1961. The newspaper was published monthly until May 1963, when Ginwala was expelled to Great Britain, likely due to conflicts with the Tanganyikan authorities. The newspaper’s proclaimed mission was to discuss questions pertaining to the politics of the continent and to “build bridges from Cape to Cairo, from Dar es Salaam to Accra” with a clearly Pan- African and anticolonial standpoint. In the first of three regular sections, Spearhead provided “News” from all over the continent. In its regular second and third sections, it tackled all the major political themes of the early 1960s. In “Views,” and the “Seminar,” it discussed the best forms of democracy and trade unionism for postcolonial contexts, as well as African socialism, Pan-Africanism, and liberation struggles. The occasional section “Profiles” paid tribute to notable figures like Nelson Mandela, Tom Mboya, or Hastings Banda. In the same spirit as other Pan-African journals produced in various African “hubs of decolonization” in the early 1960s, Spearhead discussed issues of postcolonial state-building and reported on anticolonial struggles on the continent. Yet, unlike other either fully or partially state-controlled journals such as Accra’s Voice of Africa and the Spark, or Cairo’s African Renaissance (Nahdat Afriqya), Spearhead was financially and editorially independent. The numerous advertisements in each issue certainly financed part of the newspaper’s operations. The range of sponsors included Twiga Soft Drinks, a Cantonese restaurant in Dar es Salaam, Radio Moscow and the Indian Ministry for Tourism. Letters to the editor came predominantly from Anglophone countries in East and Central Africa, although the subscription information for Spearhead was also provided to readers in Great Britain and “all other parts of Africa.” Editing Spearhead, Ginwala could draw on a wealth of experiences and her continent-spanning network. Not long after finishing her law studies in the UK and the US, Ginwala worked as a correspondent for British media. She became involved with Ronald Segal’s Cape Town-based magazine Africa South, many of whose contributors would come to write for Spearhead. They were joined by scholars and journalists such as the Guardian’s Africa correspondent Clyde Sanger, South African communist Hermann Meyer Basner or Patrick McAuslan, a radical lecturer at Dar es Salaam’s newly established Law Faculty. The publication provided a platform for high-ranking African politicians and functionaries like Kwame Nkrumah, Sékou Touré, or Ghanaian trade union leader John Tettegah to promote their views on Pan-Africanism and postcolonial statehood. Leaders of liberation movements voiced their criticisms of colonial regimes and called for support, though there were also debates on varying strategies – for instance regarding the boycott of trade with apartheid South Africa…"

Spearhead cover, Nov 1961. Presented by Katharina Föger Eric Burton. "Spearhead. The Pan-African Review was established by the South African lawyer and journalist Frene Ginwala in Dar es Salaam, the capital of Tanganyika (later Tanzania), just one month ahead of the country’s full independence in December of 1961. The newspaper was published monthly until May 1963, when Ginwala was expelled to Great Britain, likely due to conflicts with the Tanganyikan authorities. The newspaper’s proclaimed mission was to discuss questions pertaining to the politics of the continent and to “build bridges from Cape to Cairo, from Dar es Salaam to Accra” with a clearly Pan- African and anticolonial standpoint. In the first of three regular sections, Spearhead provided “News” from all over the continent. In its regular second and third sections, it tackled all the major political themes of the early 1960s. In “Views,” and the “Seminar,” it discussed the best forms of democracy and trade unionism for postcolonial contexts, as well as African socialism, Pan-Africanism, and liberation struggles. The occasional section “Profiles” paid tribute to notable figures like Nelson Mandela, Tom Mboya, or Hastings Banda. In the same spirit as other Pan-African journals produced in various African “hubs of decolonization” in the early 1960s, Spearhead discussed issues of postcolonial state-building and reported on anticolonial struggles on the continent. Yet, unlike other either fully or partially state-controlled journals such as Accra’s Voice of Africa and the Spark, or Cairo’s African Renaissance (Nahdat Afriqya), Spearhead was financially and editorially independent. The numerous advertisements in each issue certainly financed part of the newspaper’s operations. The range of sponsors included Twiga Soft Drinks, a Cantonese restaurant in Dar es Salaam, Radio Moscow and the Indian Ministry for Tourism. Letters to the editor came predominantly from Anglophone countries in East and Central Africa, although the subscription information for Spearhead was also provided to readers in Great Britain and “all other parts of Africa.” Editing Spearhead, Ginwala could draw on a wealth of experiences and her continent-spanning network. Not long after finishing her law studies in the UK and the US, Ginwala worked as a correspondent for British media. She became involved with Ronald Segal’s Cape Town-based magazine Africa South, many of whose contributors would come to write for Spearhead. They were joined by scholars and journalists such as the Guardian’s Africa correspondent Clyde Sanger, South African communist Hermann Meyer Basner or Patrick McAuslan, a radical lecturer at Dar es Salaam’s newly established Law Faculty. The publication provided a platform for high-ranking African politicians and functionaries like Kwame Nkrumah, Sékou Touré, or Ghanaian trade union leader John Tettegah to promote their views on Pan-Africanism and postcolonial statehood. Leaders of liberation movements voiced their criticisms of colonial regimes and called for support, though there were also debates on varying strategies – for instance regarding the boycott of trade with apartheid South Africa…"

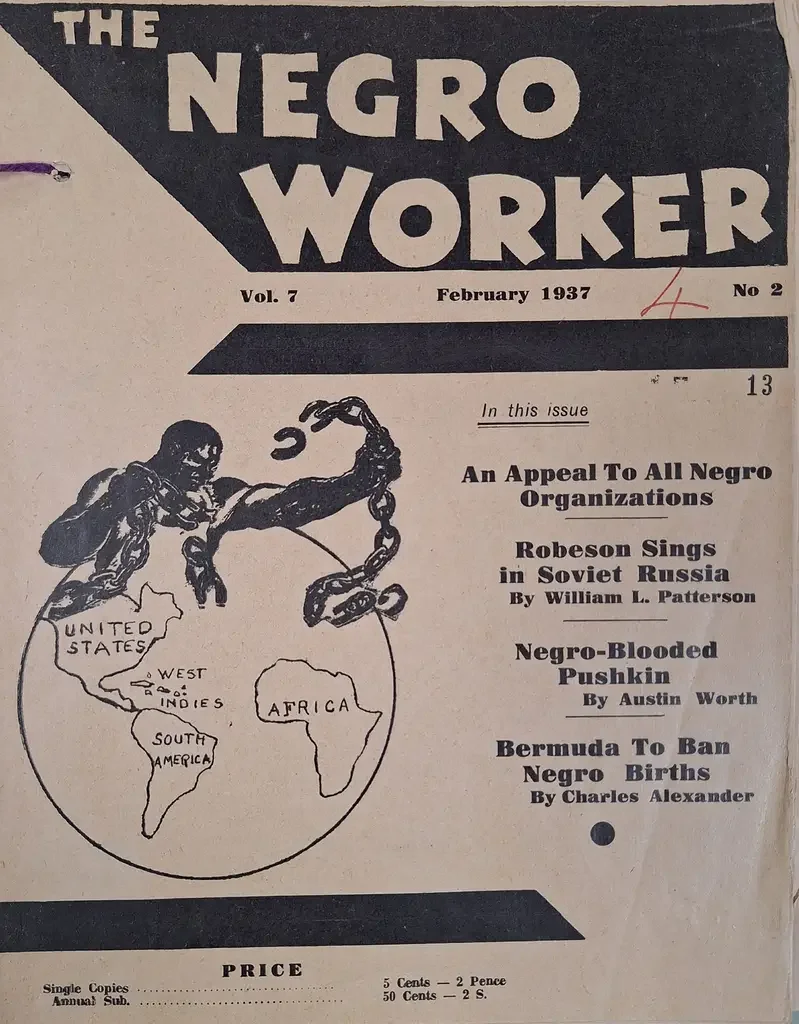

The Negro Worker The cover of Volume 7 of The Negro Worker publication, dated February 1937. Date 1937 Catalogue reference CO 323/1518/9 Published between 1928 and 1937, The Negro Worker was 'the official organ of the International Trade Union Committee of Negro Workers' (ITUCNW). Led by African American communist James W Ford, the ITUCNW aims, as listed at the back, included 'To promote and develop the spirit of international solidarity between the workers of all colours, races and nationalities.' The file includes five original copies as part of an order prohibiting the importation of the newspaper into present day Ghana and signed off by then Conservative Colonial Secretary, William Ormsby-Gore. The articles highlight a range of contemporary issues including the Italian invasion of Ethiopia as well as the implications of the rise of Nazi Germany for colonised peoples, particularly Hitler’s demands to have former German colonies returned. The parallels between colonialism and fascism are not lost on the authors.

![GB3228.34/1/2, Pan-African Congress 1945 and related celebratory events 1982-1995, Press photograph of the 1945 Pan-African Congress delegates and [Manchester City Mayor?] (1945).](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/65b41067c4042363cf11625f/7531b519-1c40-4b83-9a79-473691bfcdf8/img012-2048x1443.jpg)